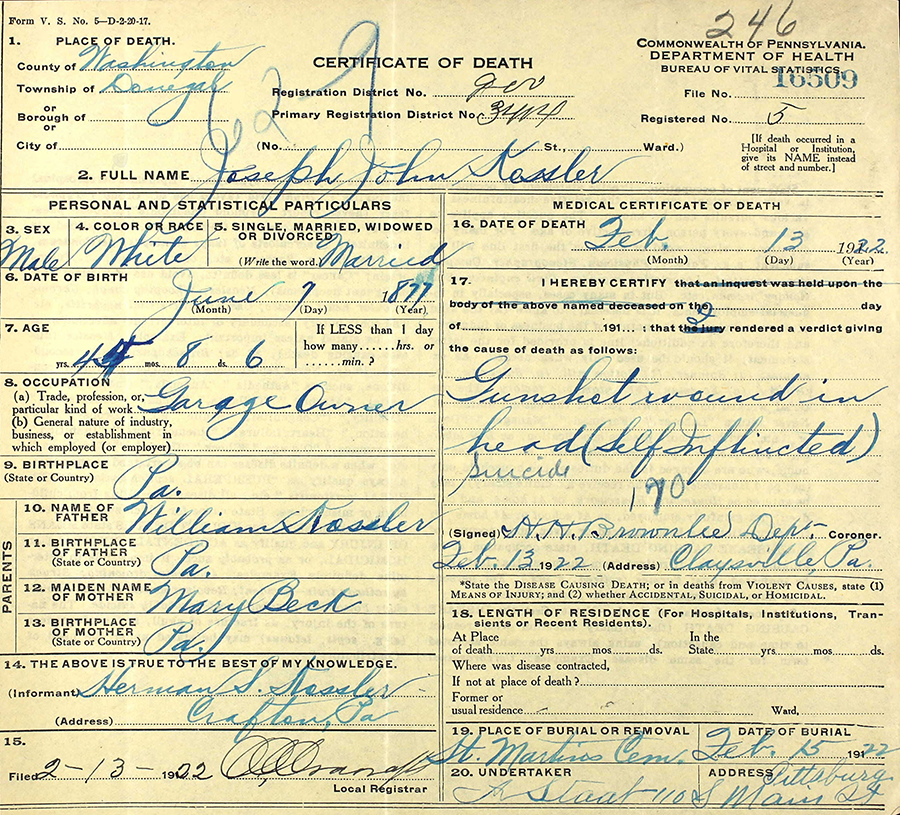

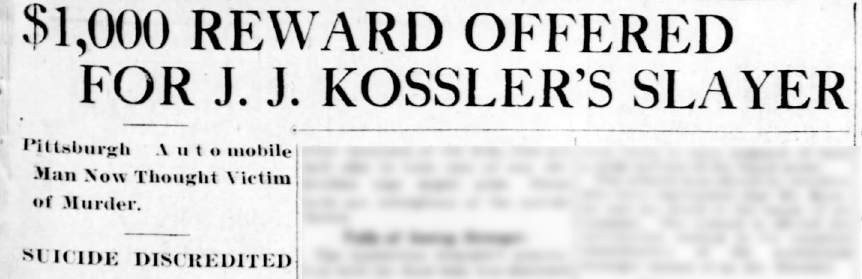

Joseph Kossler was a successful West End truck manufacturer and automobile dealer. He was a pillar in the community — or so everyone thought until he was found dead in his car from a gunshot wound to the head in February 1922. Adolph Hertig, a farmer who lived in West Alexander, Washington County, found Kossler’s car and body in a lane leading to a neighbor’s home. Kossler’s family was adamant that someone had killed him. They even hired an outside investigator after officials intimated that Kossler’s death would be ruled a suicide. Ultimately, that’s what the Washington County Coroner listed in Kossler’s death certificate as the cause of death: “Gunshot wound in head (self-inflicted).” The coroner emphasized his finding on the next line, “Suicide.”

If Joseph Kossler didn’t kill himself, who did? Was it one of his many creditors? Was it the family of a young girl Kossler hit and injured in a car accident? An angry customer? Or, could it have been the bootleggers who used Kossler’s commercial garage to store their booze? Any one of these scenarios offers a plausible alternative to suicide.

So, who was Joseph Kessler and how did he end up dead along a rural road about 12 miles west of Washington, Pa.?

Joseph Kossler

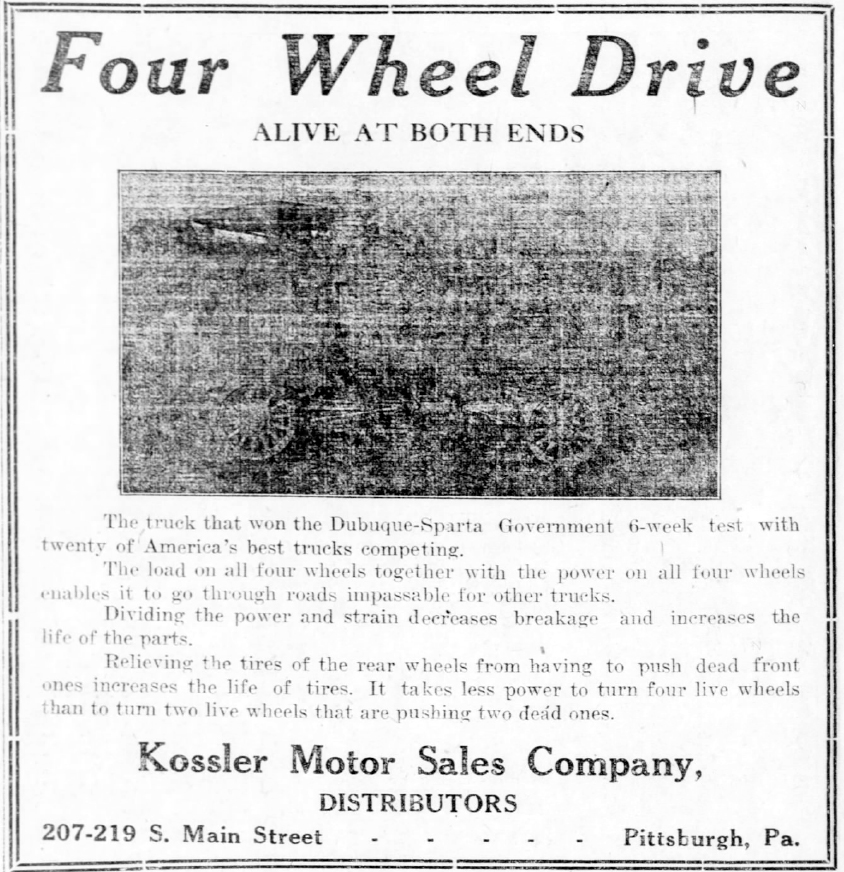

Joseph Kossler was born in Pittsburgh June 7, 1877. His father, William, was a farmer who went into the hardware business in the West End. In 1899, Joseph (at that time, calling himself John J. Kossler) married Minnie Roberts. The couple moved into the Kossler family home on Wabash Street. Kossler initially worked in several jobs, including as a salesman and electrician, before founding his own business, the Kossler Motor Company, selling trucks in the 200 block of South Main Street in the West End. In 1918, Kossler vertically integrated his automotive business, buying the Ohio-based Niles Motor Truck Company and moving its plant to the West End. The firm specialized in building trucks engineered for Pittsburgh’s hills and they were sold through Kossler Motors.

Joseph and Minnie raised six children on Wabash Street. Up until 1922, the family appeared to live an uneventful life. Mrs. Kossler’s name occasionally appeared in various society page events reports. Joseph’s name appeared infrequently in the newspapers. In 1925, he was injured while removing a wrecked car: the block and tackle he was using broke. When Kossler bought the Niles Motor Truck Company, the Pittsburgh Press described him as “a well known automobile man in Pittsburg.”

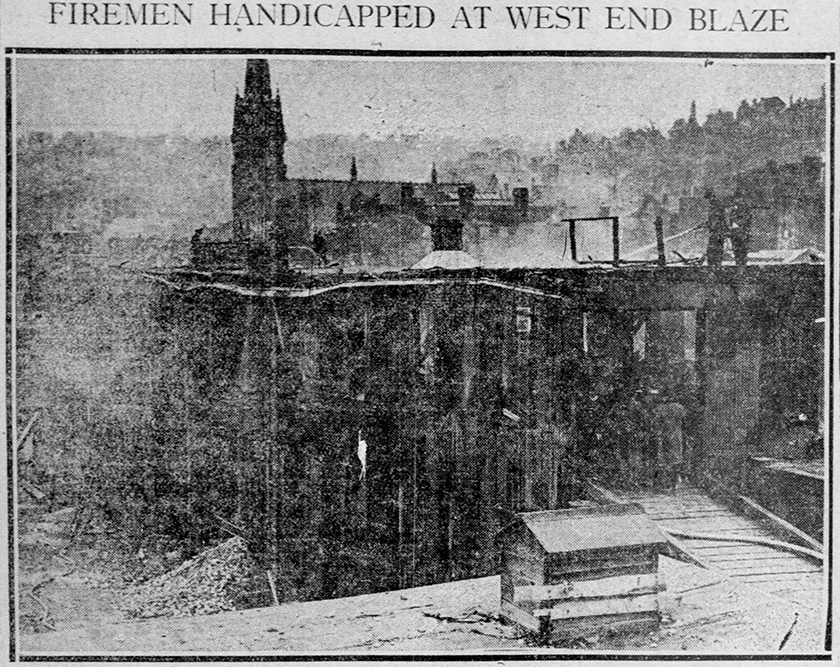

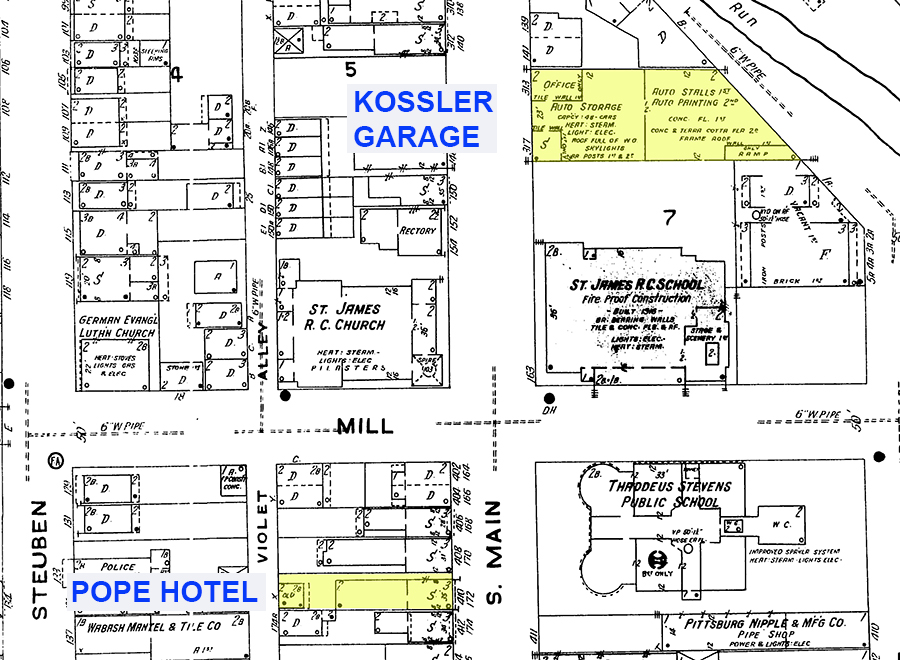

From the outside, it looked like business was good. In May 1919, a fire swept through a warehouse at 117 S. Main Street. Kossler rented space there to store cars and truck parts. Another tenant stored paint there and it ignited, destroying Kossler’s inventory valued at $50,000. In need of new garage space, one month after the fire Kossler bought three adjacent lots at 313-317 S. Main Street. He paid $4,000 cash for the real estate and hired contractors in 1921 to build a large two-story garage there.

Kossler borrowed money to pay $12,000 for the garage construction. Commercial garages were just taking off nationally as the number of automobiles on city streets exploded. To help pay off the costs to build the garage and generate additional income, Kossler rented space in the garage to several individuals, including painter Bernard Mansfield who did business on the building’s second floor. Kossler used the remainder for his automotive business.

Was it Robbery?

Family members told newspaper reporters that Kossler left home the day he died with $60 and he had 48 cents on him when authorities recovered his body. “That he was murdered for this money by some person whom he picked up along the road to give a ride is the belief held by some of his friends,” reported the Pittsburgh Press.

The robbery theory was quickly dismissed, however, with no details reported in the newspapers.

Was it a Creditor?

Joseph Kossler’s probate records contain a laundry list of business and personal creditors. There were claims against Kossler’s automotive business arising from faulty equipment and contractors looking to be paid. There were loans to be paid and utility bills. Kossler had hit and injured Gertrude Lear while driving his car. At the time Kossler died, the young woman’s family was seeking damages on her behalf (the estate paid a $300 settlement).

On the new garage alone, Kossler owed more than $20,000 on top of the mortgages attached to the property. There were unpaid bank notes and bills from parts suppliers. Kossler’s assets included $87 cash deposited in the bank, a King Roadster car, and about $2,000 in stocks and bonds. His personal assets also included lots of tools and equipments used in the automotive business, office furniture, and two cash registers. On paper, Kossler had about $7,600 to his name. Kossler owed his creditor a lot more than that.

Yes, Joe Kossler was in a deep financial hole, but there’s an old maxim among mobsters: dead people don’t pay. No, there’s no evidence that Kossler was a mobster, but the idea still applies.

Did Bootleggers Kill Kossler?

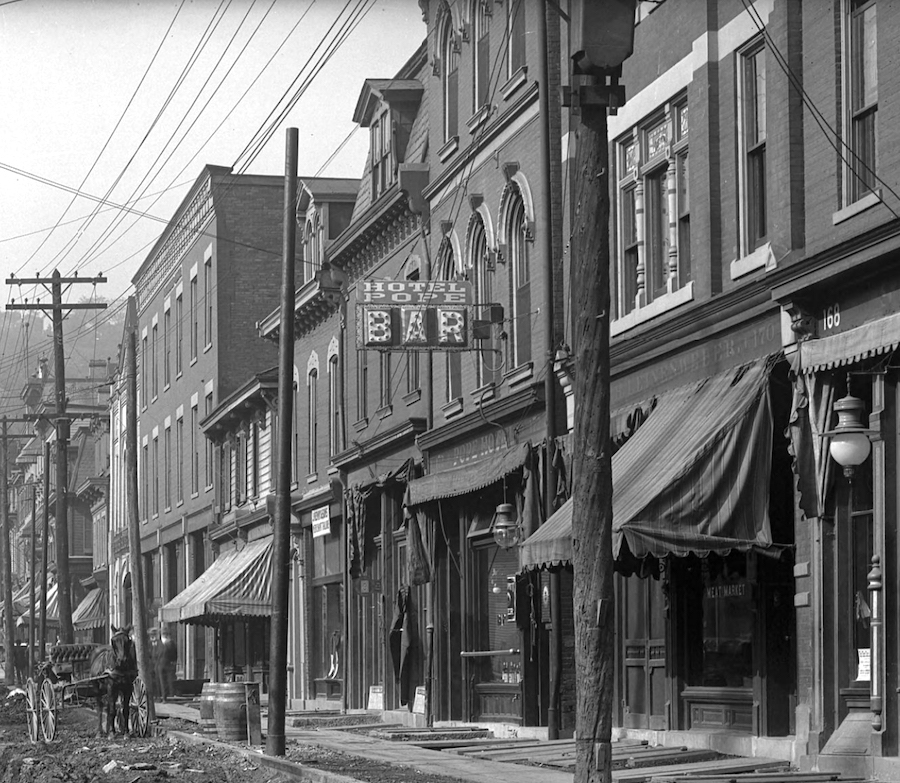

Leo Pope, the son of hotel- and saloon-keeper August Pope was one of Kossler’s garage tenants. In 1910, August Pope had bought the liquor license and business assets of the Hay Hotel at 172 S. Main Street, one block away from Kossler’s auto business. Kossler’s new garage was two blocks up Main Street from the Hotel Pope. Leo Pope rented one of 14 spaces inside the garage where he claimed that he used the space to repair, store, and sell cars.

After four months of surveillance and investigation, in late 1920 federal Prohibition agents raided Pope’s hotel. They arrested August, seized his liquor, and padlocked the establishment. Pope’s conviction earned him a dubious place in Pittsburgh history: the press reported that his conviction marked the first time that a Prohibition law violator received a substantial fine and jail time: the court hit Pope with a $1,000 fine and sentenced him to one day in jail. Freda Pope, the alleged “brain” behind the family’s bootlegging ring, would later become one of Pittsburgh’s best-known women nightclub owners. Her resume included running the infamous Show Boat for three years in the 1930s.

In their investigation, federal Prohibition agents learned that the Popes used Kossler’s garage. When they arrested August, Leo, Henry, and Freda Pope, they also raided Kossler’s garage at 313-317 S. Main Street and seized 200 cases of whiskey, 11 kegs of “vinous and spiritous intoxicating liquors,” and 50 bottles of “assorted intoxicating liquors.” It was quite a haul and the federal government threw the book at the Popes.

A federal court convicted all of the Popes for selling liquor and for conspiring to sell liquor. They appealed, arguing that the convictions were tainted by bad evidence and procedures. After more than a year and a new trial, the court overturned Freda Pope’s conviction. Would Kossler have provided testimony damaging to the Popes or could he have helped them? With Kossler out of the way, there was no one to speak to his arrangements with the Popes or what he might have known about their activities inside the garage.

The Search for a Killer

Lacking a suicide note and credible leads that squared with Kossler’s reputation, speculation about his death made headlines throughout February 1922. The Post-Gazette had reported that Kossler “had not been in good health, suffering from heart disease.”

Reports about Kossler’s financial health also began circulating. “Joe Kossler had some financial obligations, E.H. Croyle, Kossler Motor Truck Company manager told a newspaper reporter. “But none of them were pressing. They were just such obligations as any man doing business on the scale done by Kossler necessarily must have.” Yet, Washington County detectives found papers with Kossler’s body indicating that he was in dire financial straits.

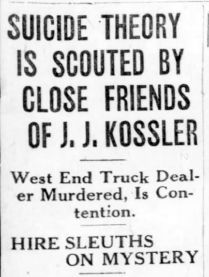

Kossler’s business associates didn’t accept the emerging explanation for the businessman’s death: suicide. “Business associates and friends of the truck dealer are … emphatic in declaring their belief that Kossler was the victim of foul play and not of self-destruction,” the Pittsburgh Daily Post reported on Feb. 18, 1922. The article described efforts Kossler’s friends and business associates took to get to the bottom of his mysterious and sudden death along a rural road. They hired private detectives after dismissing Kossler’s financial obligations and health problems.

The suicide skeptics hinted at a motive for Kossler’s alleged murder but they never revealed it publicly. “There was a far deeper motive [behind] the alleged murder, those in close touch with Kossler’s affairs declare,” wrote the Pittsburgh Daily Post. Kossler’s associates asserted that he was taken for a drive, his whiskey drugged, and then shot by people “who wanted Kossler out of the way.”

Did the Popes want Kossler “out of the way” as their appeals worked their way through the federal courts? It’s unlikely. There is no evidence that the Popes used violence to dealt with problems. Arson, maybe — at least two of their roadhouses burned down following litigation initiated by landlords. But murder? It’s unlikely and it doesn’t fit the bootlegging family’s profile.

Though the newspaper reports lacked important details and the Washington County coroner didn’t convene an inquest, the reasons why Kossler killed himself may be found in the voluminous probate records filed in Allegheny County Orphan’s Court. Kossler died intestate and it was up to his family to work through the financial mess that he left and settle the estate. The court appointed Joe’s older brother, Frank, executor. It took three years to settle Kossler’s affairs. Poring over unpaid bills and claims against Kossler, accountants found that he owned more than $88,000 and the judge declared the estate insolvent. The court ordered Kossler’s assets to be sold to satisfy the debts. A final accounting filed in the case determined that Kossler’s creditors only received $2,777 in cash payments.

February 13, 1922 and Afterwards

The evidence for suicide was overwhelming. Kossler was in debt and his health was failing. Joseph Kossler got into his car with a bottle of whiskey and a handgun. He drove about 40 miles from his home to an isolated farm lane west of Washington, Pa. Kossler drank about half the whiskey in the bottle and then put the barrel of the gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger. Hertig found Kossler’s body and summoned the authorities. Washington County Deputy Coroner Harry “H.H.” Brownlee retrieved the body and brought it to his Claysville funeral home, where he examined it and determined the cause of death to be suicide by self-inflicted gunshot.

Kossler’s relatives identified and retrieved the body. Kossler’s South Main Street neighbor, Anthony Staab, handled the funeral and burial in Pittsburgh’s St. Martin’s Cemetery. In an ironic twist, Staab bought Kossler’s garage at 313-317 S. Main Street and used it for his mortuary business.

Minnie Kossler continued to live in the West End at 148 Wabash Street. The house was demolished long ago and there’s now a parking lot where the Kosslers once lived. In 1928, she and 36 others were indicted on charges of election fraud. She denied any wrongdoing and negligence. An Allegheny County court convicted 21 people, including Minnie. She escaped jail time and got two years probation. By 1930, she was working as a Pittsburgh Police “matron.” In 1948, Minnie married widower Maurice Hart and she moved from the West End. She died in 1956 at age 83 and was buried next to Joe.

So who killed Joe Kossler? It looks like the coroner was right all along: Joe Kossler killed Joe Kossler.

©2023 D.S. Rotenstein