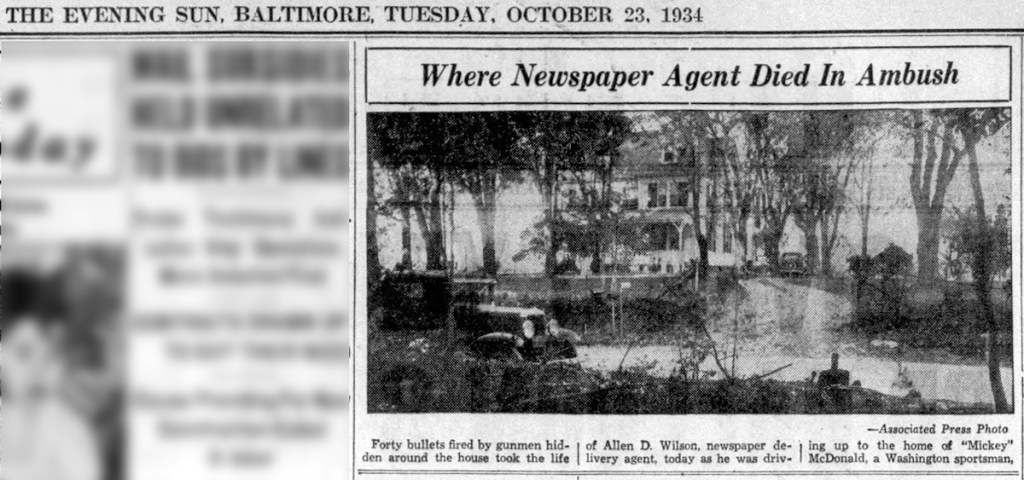

Obsessed is probably too strong of a word to describe my interest in the October 1934 turf war among two Washington, D.C. gambling entrepreneurs. But, I have had a very keen interest in the case ever since 2019 when I first read about it while working on the Talbot Avenue Bridge Historic American Engineering Records (HAER) report. It had been nearly four years since my first interviews with an aging Washington, D.C., former journalist had turned me onto the historical significance of numbers gambling. By the time that my research took me to the Takoma Park, Md., driveway where a notorious mob hitman gunned down newspaper employee Allen Wilson, I was hooked.

On July 25, I’m continuing the mini-mob-lecture circuit with a talk on racketeering in the D.C. suburbs: “The Numbers Game in the Burbs: Racketeering in Montgomery County.”

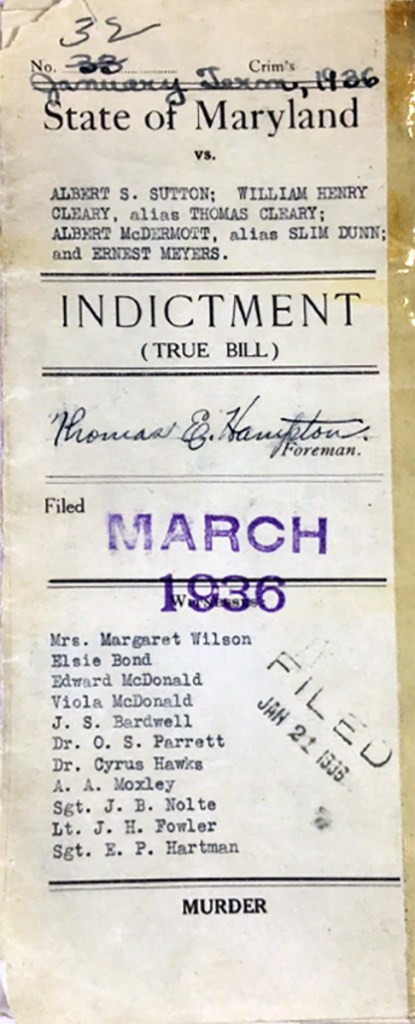

The free virtual program covers the history of racketeering and numbers gambling in the D.C. burbs, from the Black gambling entrepreneurs who ran the numbers in rural African American communities throughout the mostly rural suburban county to the white D.C. kingpins who made their homes there to complicate law enforcement efforts to rein them in. The so-called “Mistaken Identity Murder” caps the program as I connect the dots on one of the D.C. area’s most sensational gangland killings.

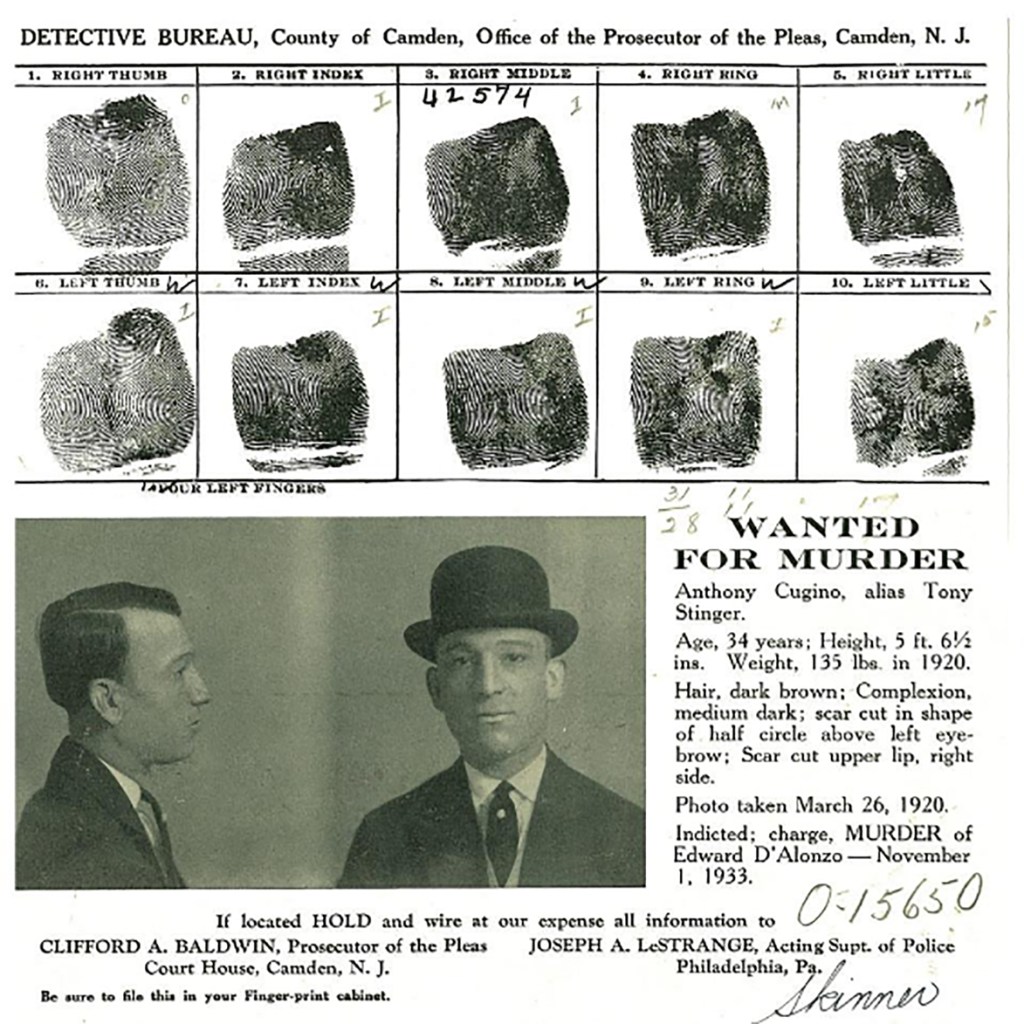

The alleged hitman, Tony “The Stinger” Cugino, was one of the East Coast’s most feared killers. In my “Squirrel Hill by the Numbers” walking tours, participants visit the site where Cugino allegedly dumped the body of one of the loose ends he cleaned up earlier in 1934 before killing Wilson. With Cugino, it’s always “allegedly” because he never made it to trial, for the Wilson murder or any of the others attributed to him. The official reports were that he hanged himself in 1935 in a New York City jail cell after the police finally caught up with him. By that time he had been suspected in hits all throughout the mid-Atlantic and upper South, including another infamous Montgomery County murder case (the “Chevy Chase Car Barn Murders“) just a few months after Wilson’s “Mistaken Identity Murder.”

Come for the numbers history and stay for the murder!

Beyond the Zoom room

The Silver Spring program is the second of three lectures on racketeering history I’m giving this month. Pittsburghers can drop in on “Cold Storage and Real Luck” at the Lawrenceville Historical Society July 20. There were mobsters on 1500 block of Penn Ave. in Pittsburgh and the story of the city’s giant refrigerator building and Pittsburgh’s most aptly named bar has several good rackets chapters.

On August 1, just a few days before Pittsburgh’s infamous 805 episode‘s 92nd anniversary, I’m speaking to the Moon Township Historical Society. Tony “The Stinger” and his 1934 visit to Pittsburgh may or may not be on the program but lots of Steel City vice will be.

© 2022 D.S. Rotenstein