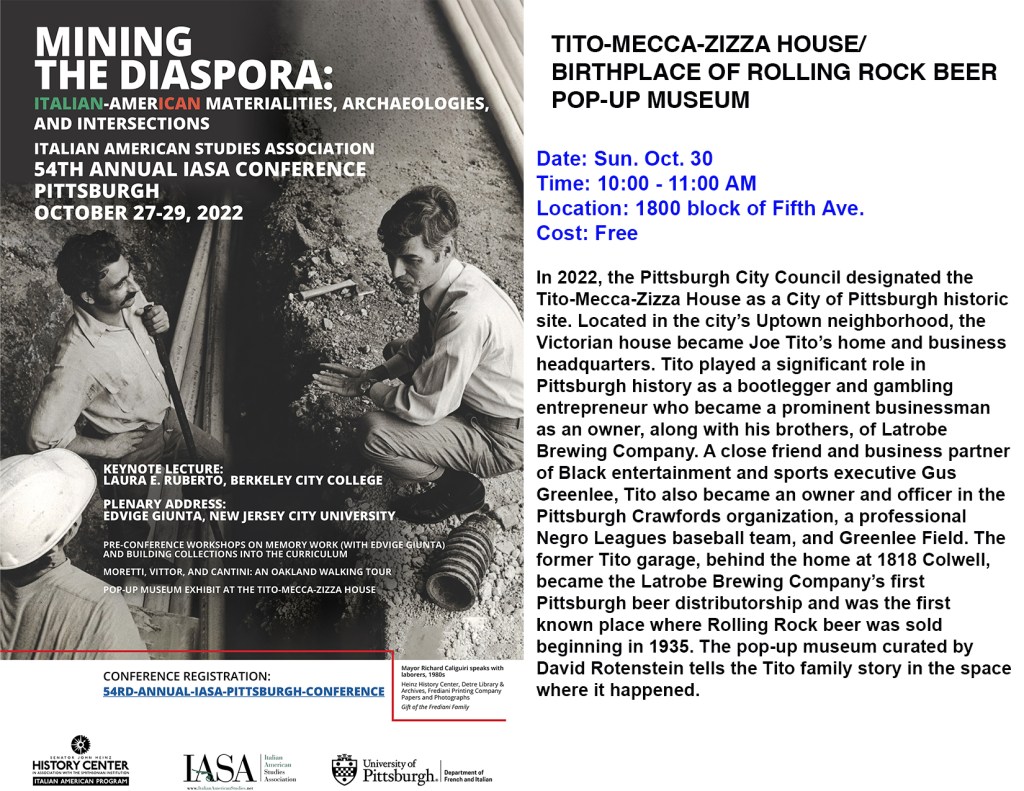

For much of the twentieth century, numbers gambling defined much of the Hill District’s economic and social landscapes. The street lottery immortalized in August Wilson’s plays and Hill District oral traditions arrived in Pittsburgh in the early 1920s. Within a decade it had spread from Hill District barber shops, pool halls, and newsstands to every corner of the city. It spawned legends and it financed the rise of the city’s rich entertainment and sports industries.

Informal lotteries thrived in Black communities since at least the 1860s. The most popular, known as policy, evolved from betting on the outcomes of official state lotteries. Later gambling entrepreneurs opened betting parlors where people could bet on combinations of digits on buttons or balls drawn from burlap bags and wire cages. Pittsburgh newspapers began reporting on policy rings here during the 1870s.

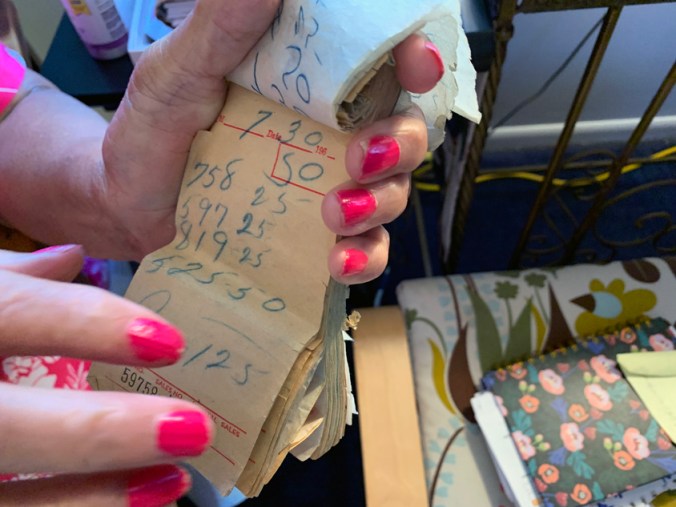

Policy, however, was easy to rig and cheating was rampant. Thus, Harlem numbers racketeers developed a system for calculating the number that players believed was incorruptible, i.e., it couldn’t be fixed like earlier street lotteries. Instead of being drawn from a container, the daily number was based on a known figure published in the financial pages of daily newspapers – popular choices included the volume of shares traded on the New York Stock Exchange, or the daily balance of the U.S. Treasury. Bettors played the game by simply selecting a three-digit number and paying a penny, nickel, or dime to a bookie called a “runner” who recorded the the number on a slip of paper. Because the daily number was unpredictable and publicly-known, consumer confidence and participation soared.

Continue reading