Originally published in the November 2022 issue of The African American Folklorist.

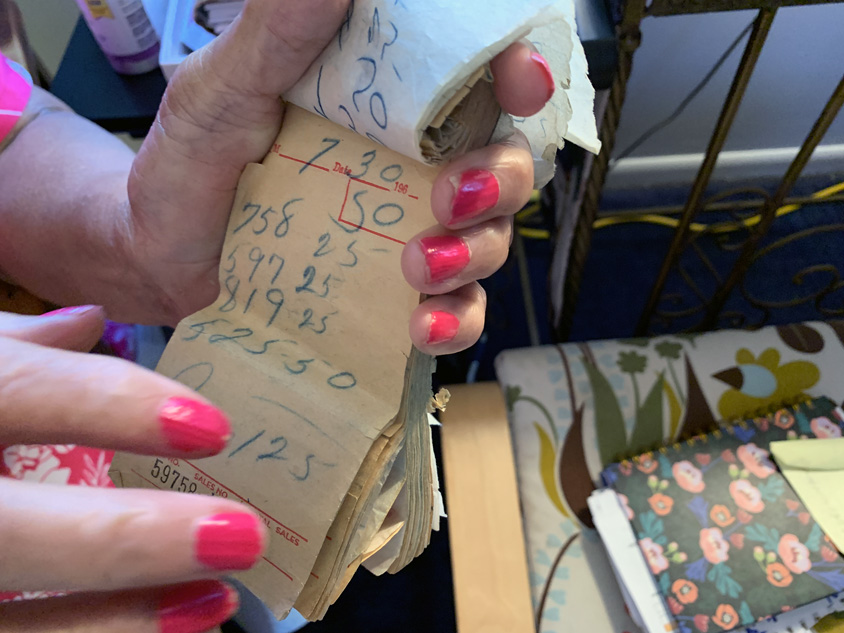

Michelle Slater loves history. That’s a good thing because her family’s story is woven into Pittsburgh’s Hill District’s history about as tightly as one can get. Slater’s grandmother wrote numbers for some of the Steel City’s best known numbers bankers. Her father cut hair and eventually ran the Crystal Barbershop, one of the Hill’s most iconic third places and Black-owned businesses. Slater, 58, herself learned the hair trade watching her father and she eventually became a licensed barber herself. That’s right, not a hairstylist, a barber. One wall inside her shop is dedicated to telling her family and community’s stories. There’s a lot to unpack inside Slater’s shop and her stories.

I met Slater while researching the social history of numbers gambling in Pittsburgh. Her father, Harold Slater (1924-2014), had cut the hair of a gregarious and well-loved numbers banker and nightclub owner, George “Crip” Barron (1924-2001). On Saturdays, Barron spent time with Angela James, whom he treated like a daughter. Barron would drop Angela off at the Hurricane bar next door to the Crystal Barbershop where she would drink Shirley Temples while he tended to busines and to his hair. After I interviewed Angela James for the first time in January 2021, she connected me to Michelle Slater.

Before I get into Slater’s story, it’s important to underscore the significance of the two intersecting traditions that dominate it: numbers gambling and barbering. Invented in Harlem in the first decades of the twentieth century, numbers gambling was a street lottery that formed the economic engine sustaining many twentieth century urban, rural, and suburban Black communities. The game enabled multitudes of small bettors to wager pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters on three-digit numbers derived from financial market returns published in daily newspapers.

With payoffs at 600-to-one, a big hit could yield anything from a dinner out to a down payment on a house. That’s how the late Colin Powell’s family bought its first home. Most gamblers, however, weren’t lucky and many found themselves betting money that otherwise would have gone towards rent and food. Numbers played off a dream of Black freedom and prosperity with long roots in this nation dating back at least to carpenter Denmark Vesey’s 1799 lottery win that enabled him to buy his freedom in South Carolina.