A shorter version of this article originally appeared in the Fall 2022 edition of the Reporter Dispatch, the newsletter of the Allegheny City Society.

Pittsburgh writer and North Side resident Bette McDevitt received the 2022 William Rimmel Award. Bette writes about Pittsburgh history and her “Neighborhood Stories” columns appear in the Sen. John Heinz History Center magazine, Western Pennsylvania History. Though Bette grew up in New Castle, her family has deep ties to the North Side.

At the May 4 annual meeting, Allegheny City Society President David Grinnell introduced Bette. David explained how he first met her while he worked as an archivist for History Center predecessor, the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. Just before the awards ceremony, David reinforced the meeting’s theme, storytelling, by inviting attendees to pick a theme from cards placed on each of the tables inside Riverview Park’s Chapel Shelter. Each person then was asked to tell a story related to a theme.

Bette’s story at her table and in her Rimmel Award acceptance speech drew from memories of Pittsburgh’s once rich numbers gambling culture. Numbers is an informal and illegal daily street lottery that arrived in Pittsburgh in the 1920s. It was an African American invention introduced in Harlem in the years just after the turn of the twentieth century. The game relied on a three-digit number derived from daily financial market returns published in daily newspapers. If bettors picked the correct three-digit number, they could convert a nickel into $30 and a dime into $60 — much more than the average pay for many Pittsburgh residents.

The numbers racket supported a large ecosystem of racketeers — runners, writers, and bankers — as well as people who owned the front businesses that doubled as numbers stations: barbershops, cigar stores, and pool rooms. These folks handled the racket’s supply side; housewives, millworkers, and city employees comprised a large pool of potential winners looking for just one big “hit.”

The North Side had its share of infamous numbers bankers, including Jack Cancelliere (who owned the longtime mob hangout, the Rosa Villa restaurant at East General Robinson and Sandusky Street) and Phil Lange whose exploits including backing the ill-fated Guyasuta Kennel Club in O’Hara Township the summer of 1930. And, Art Rooney — a close Lange partner and friend — was the biggest gambling boss of them all with gambling joints and speakeasies in several North Side locations.

Bette’s family wasn’t part of that crowd.

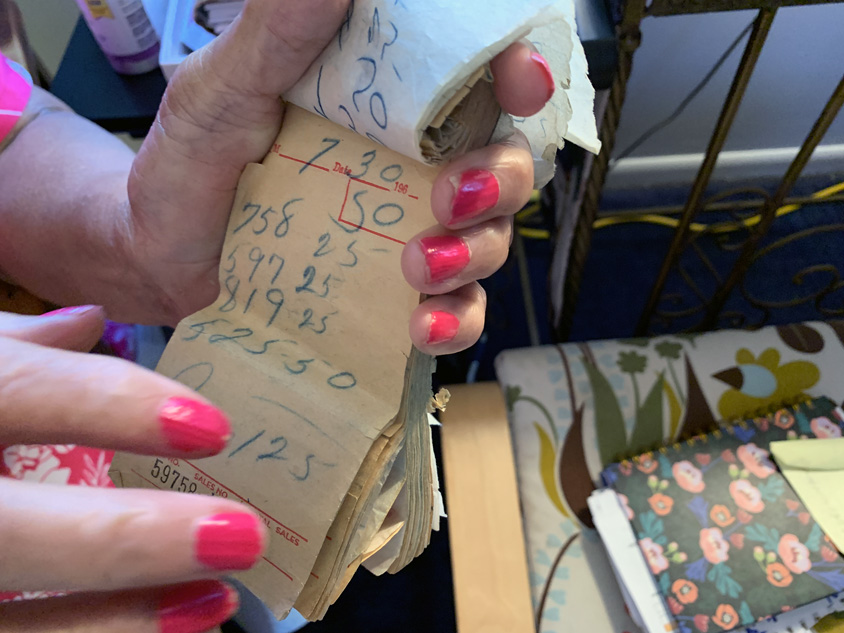

At the May meeting, Bette recounted a summertime visit during the 1940s to her aunts and grandmother, who lived in a house on Brighton Place. Bette was about 12 years old at the time. She described being handed some coins wrapped in paper with a note instructing the numbers writer down the street how to play the bet.

“Three women, plus my grandmother, who was an important person there — they all played the numbers,” Bette recalled in a subsequent telephone interview. “They all played the numbers and in the morning when they woke up, they got the dream book out to see which numbers they should play.”

Bette remembered taking the bet to a Charles Street store. Bette’s Aunt Jen usually took the daily bet. “One day, she told me that I could do that and be the runner,” she said.

Like many Pittsburgh families, numbers was an important part of daily life in Bette’s family’s household. Her aunts and grandmother lived in an apartment above a barbershop run by a man named Henry. “He used to come up the steps every day to the apartment and stand on the top step and he would ask, ‘What was the number today?’”

Playing the numbers was just another daily routine, like cooking dinner, grocery shopping, or picking up the mail. After we spoke, Bette dug into her family records and came up with some letters written by her grandmother. She quoted one to me in a May 2022 email. “Doris was lucky on the numbers,” Bette’s grandmother wrote about her other granddaughter, Bette’s sister. The letter, signed “Mum,” continued,

Called me on Monday play 108 ten cents a day. It came up the same day. So she told me to keep the 4 dollars. I sent her the fifty dollars. So the next week she called again play 315 ten cents a day came up the second day she played it. Sent her fifty dollars again. Irene had it too. Won two days straight. Doris said she figured out when her baby would be born it was 315. I buy a treasury ticket every week. If you have the whole five numbers you win eleven hundred dollars. I play every day. So it came out in the paper 26632. I had 20632 I got 5 dollars for the last three numbers. Sometime I may get it. Doris sure cleaned up. Got the ten-cent jackpot. Ed got the 5 cent one. Mother 60 dollars on the crap. Poor Dad nothing. Rose Mary is going to be operated on Sat. I’ll say good-by with love to both of you.

Though Bette only spent one week in the apartment that summer, the experience made an indelible mark in her memory. That memory is now part of a polished storytelling repertoire. Bette explained, “When I do tell people that, it seems so unlikely to them, you know, this white-haired old lady that was a messenger or whatever it’s called. It gets a great reaction from people because it’s out of character for me.”

Bette also credits those fond memories for influencing her move to the North Side. Like many good historical storytellers, Bette uses the built environment to teach people about the past in an entertaining way. “I moved here, to this neighborhood, probably because of all the good memories I have from being around here,” she confessed in our interview. “I can find family sites all over the Northside.”

© 2022 D.S. Rotenstein