A Family Business

Nineteen thirty-two was a turbulent year in Pittsburgh organized crime history. Prohibition was winding down and the city’s racketeers were positioning themselves in a world where liquor and beer would again be legal. Turf wars in the Steel City were local dramas set within a larger story where such racketeers as Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Meyer Lansky were solidifying their hold over a national organized crime syndicate (frequently dubbed La Cosa Nostra). In 1931, Luciano became the syndicate’s leader following the brutal murders of Joe “The Boss” Masseria and Salvatore “Boss of all Bosses” Maranzano. Giuseppe “Joe” Siragusa, Pittsburgh’s “Yeast Baron,” was brutally killed in his Squirrel Hill home that year. Assassinations and violent warnings were the tools of the trade.

Joe Tito (1890-1949) was a major figure in Pittsburgh’s rackets by the time Luciano formed his commission and national vice network. He was born in Bloomfield and had grown up in Soho, where his father Raphael had bought several properties on Gazzam Hill starting in the mid 1890s. On paper, Raphael worked as a street lamp lighter, but his rapid rise from Bloomfield renter to Soho landlord, suggests some off-the-books enterprises. A number of “Black Hand” bombings and threats involving people living in his properties offers some hints as to what the source of his wealth might have been.

Joe was one of eight children Raphael and Rosa Tito had in Pittsburgh: three daughters and five sons. Before Prohibition, the Tito boys — Joe, Frank, Anthony, Ralph, and Robert — worked in various jobs. Frank had run a poolroom and briefly worked as a Pittsburgh police officer. His brothers were hucksters selling vegetables in city streets, according to family stories.

Prohibition went into effect in January 1920 and by late 1922, the Tito brothers were making headlines for their involvement in local bootlegging operations. About the same time their names began appearing in county and federal criminal dockets, Raphael and Rosa bought a stately Victorian home at 1817 Fifth Avenue in Uptown. Though the property was in their name, Joe moved in soon after the deal closed.

Also in 1922, the Titos built a large two-story garage at the rear of the property fronting on Colwell Street. They used the garage to house the fleet of trucks used in their bootlegging operations and, presumably, in the legal hauling business they conducted under the firm name, “Tito Brothers,” according to city directories.

The Volpe Massacre

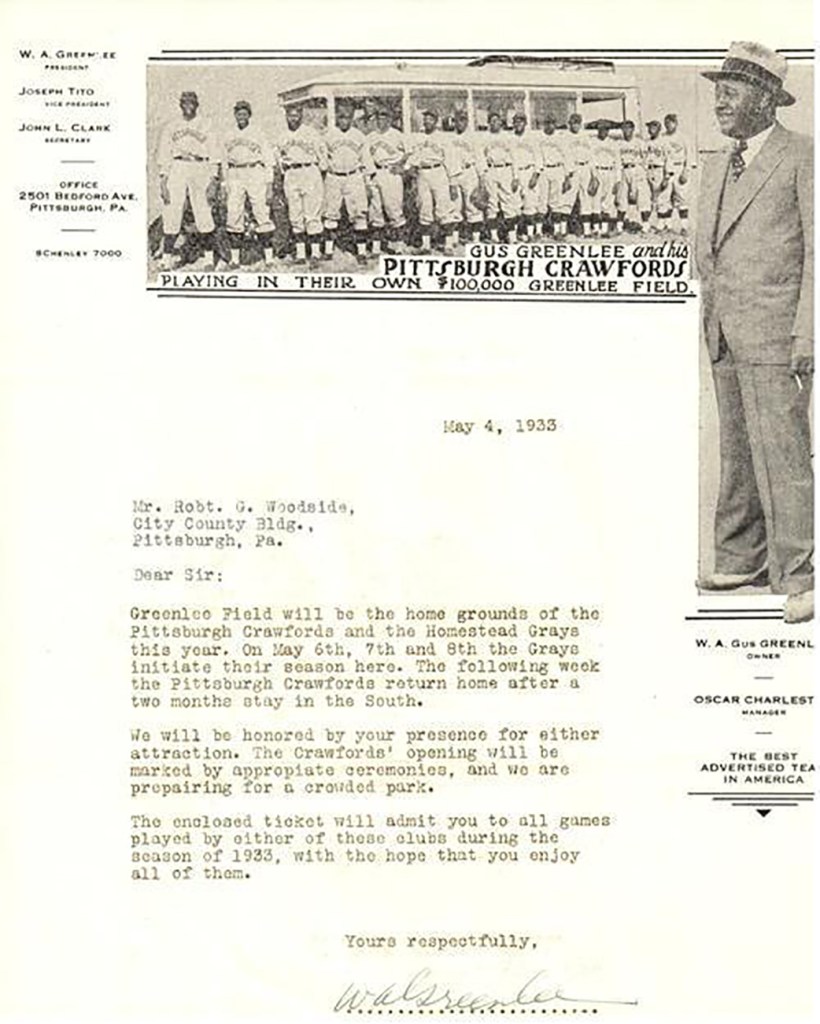

Joe was the oldest and he appears to have been the family’s Prohibition-era leader. By 1931, Joe Tito was well recognized as one of Pittsburgh’s top echelon bootleggers. Like his counterparts throughout the city and nation, he also got into numbers gambling in the mid-1920s. Gus Greenlee, an African American who came to Pittsburgh during the Great Migration, was one of Joe Tito’s closest friends and associates. He also was an entertainment entrepreneur: a bootlegger, nightclub owner, and boxing promoter who many historians credit with being one of four men who introduced numbers gambling to Pittsburgh. In early 1932, perhaps in anticipation of Prohibition’s end, Greenlee and Tito along with another boxing promoter, Thomas J. Higgins, filed papers to incorporate the Negro Leagues baseball team that Greenlee had recently bought: the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Greenlee became the new corporation’s president; Tito its vice president; and, Pittsburgh Courier columnist John L. Clark became its secretary.

Baseball wasn’t the only thing on Joe Tito’s mind in early 1932. Luciano’s exploitation of fault lines among leading racketeers and his consolidation of power in cities from Chicago and Detroit to New York and everywhere in between must have been part of Tito’s calculus as he and his brothers began planning for a post-Prohibition economic landscape that included legal booze. Prohibition ended in 1933 and the Tito brothers invested in a dormant brewery that had been part of the sprawling Pittsburgh Brewing Company’s empire, the Latrobe Brewing Company. The brothers and their brewery became well known for introducing Rolling Rock beer.

One episode from 1932 firmly fixed Pittsburgh’s place in mob history: the July 29 slaughter of Arthur, James, and John Volpe in a Hill District coffee shop. Joe Tito was one of the last people seen with John Volpe. He had offered to pay for Volpe’s lunchtime haircut because all that Volpe had was a $10 bill. Volpe left the Fifth Avenue barbershop and Tito and headed up to the Rome Coffee Shop on Wylie Avenue. There, three gunmen opened fire killing the Volpes. The story has become enshrined as a key piece of Pittsburgh organized crime history canon.

Pittsburgh police hauled Tito in for questioning. “Racket King Quizzed on Volpes,” read one headline in the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph on August 2, 1932. “Joe Tito, friend of the Volpes and reputed kingpin of two rackets—beer and numbers— was questioned by homicide detectives.” Tito also was a viable suspect because word on the street was that the Volpes had begun infringing on his Hill District and Oakland territory.

Joe Tito clearly occupied a prominent position in Pittsburgh’s organized crime hierarchy. By 1932, he was one of the city’s leading racketeers. Newspapers reporting on his questioning in the Volpe triple murder case recognized that he was a special case. The Post-Gazette reported that Tito was shown “special consideration” while being questioned: “His entrance and exit were made with the utmost concern for his privacy,” the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported.

Tito and John Bazzano disappeared after the investigation into the Volpe massacre ramped up. Armchair crime sleuths have tried to connect Tito with Bazzano’s ill-fated trip to New York, where his bound and mutilated body was found dumped less than two weeks after the Volpe murders. Bazzano had been “invited” to New York to attend a testimonial dinner in his honor, according to police informants. Instead of feting the new Pittsburgh beer boss, Luciano’s newly formed commission reportedly made an example of Bazzano for the allegedly unsanctioned Volpe hit. Several high-ranking La Cosa Nostra founders, including Albert Anastasia (a co-founder of “Murder, Inc.”), were questioned as suspects in Bazzano’s murder. Joe Tito’s role(s) in the Volpe and Bazzano murders was never fully resolved.

Joe Gets Taken for a Walk

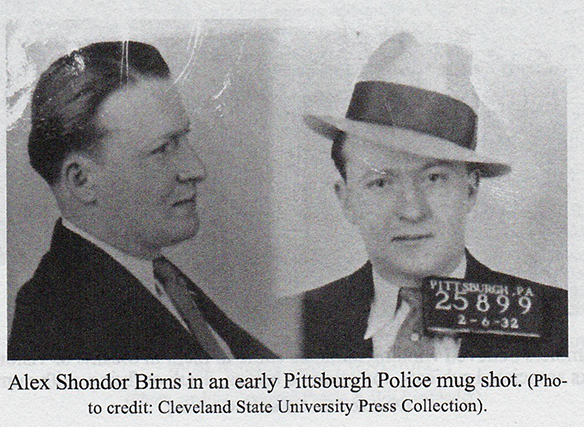

In his richly detailed biography of Cleveland racketeer Alex Shondor Birns, that city’s masterful mob chronicler Rick Porrello included a 1932 Pittsburgh Police Department mugshot of Birns. In describing some of Birns’ early brushes with the law, including robberies, Porrello wrote, “In Pittsburgh, Birns was the suspect in another robbery. By the time an arrest warrant was issued, [Birns] was back in Cleveland. He wasn’t extradited … the case was eventually discharged (pp. 38-39).

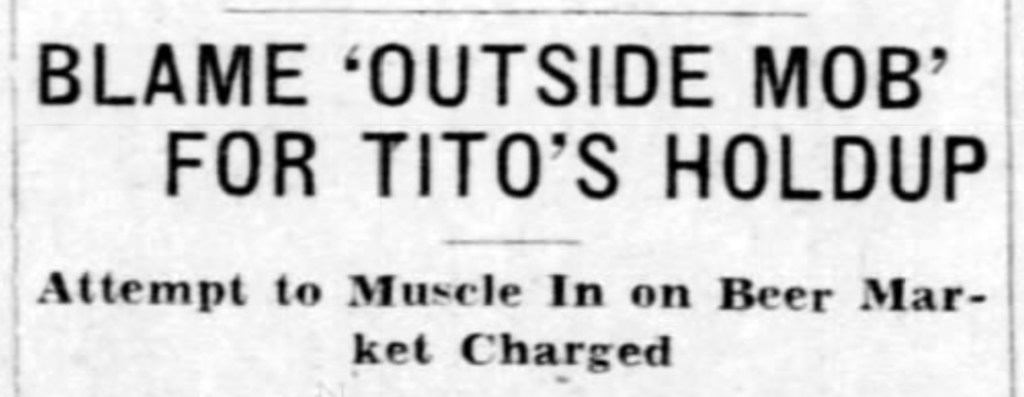

Porrello didn’t dig too deeply into that 1932 episode, however. Cleveland newspapers reported on it and Birns’s extensive FBI file has a brief mention of it. But, back in Pittsburgh, the “robbery” was big news. “Bandits Take Man For Walk,” was the Post-Gazette headline March 29, 1932. The Press had a similar headline that day: “Thugs Who Robbed ‘Beer Baron’ Hunted.”

According to the published accounts, Tito had returned home to his 1817 Fifth Avenue home after midnight Monday March 28, 1932. Two men brandishing guns grabbed him as he approached the porch. Two additional men joined the first two and they forced Tito inside the house. “Tito reluctantly gave police meager details of the hold-up,” the Post-Gazette wrote. Tito told officers that the men had stolen $600 in cash and $1,000 in jewelry. Tito also identified Birns from one of the mugshots police showed him. Tito also identified another longtime Birns associate as one of the men there that night: Arthur Miller.

As Porrello wrote, Birns and the others were never returned to Pittsburgh to stand trial and the case was dropped. Reporters speculated that an “outside mob” had been behind the crime and that its intent was to “murder him and pave the way for the entrance into Pittsburgh of a new gang of beer vendors,” wrote the Press on March 30, 1932.

Though Porrello’s account of Birns’s career was thorough, Porrello didn’t connect the February 1932 mugshot reprinted in his book with the March 1932 episode at the Tito home. On February 6, 1932, Birns, Miller, and another man were arrested on “suspicious persons” charges while on Sixth Street in downtown Pittsburgh. The men told Pittsburgh police officers that they were living in the Roosevelt Hotel. A search of their room yielded a cigar box with a hidden compartment containing 12 shotgun shells. The Post-Gazette reported, “Police said the shells are the type used in sawed off shotguns. The men were unable to account for the shells.”

Were Birns and Miller in Pittsburgh in early 1932 to kill Joe Tito or to send him a message? And, did the Pittsburgh police inadvertently foil their plans by arresting the pair downtown? Perhaps more intriguing is how, if at all, do the events on February and March 1932 with Joe Tito relate to the Volpe ambush and massacre just four months later? We may never know because all of the players are long dead and the surviving historical record offers only questions, not answers.

Beyond the Page

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette‘s Steve Mellon wrote a comprehensive and well-illustrated account of the Volpe massacre and its place in Pittsburgh mob annals: Pittsburgh, The Dark Years (2013).

Rick Porrello has written extensively on Cleveland’s organized crime history. Bombs, Bullets, & Bribes: The True Story of Notorious Jewish Mobster Alex Shondor Birns (2020) is the most authoritative source on Birns. Porrello’s 2001 book about Birns protege Danny Greene, To Kill the Irishman, was made into a movie in 2011 starring Christopher Walken as Birns.

Joe Tito’s former house at 1817 Fifth Avenue and the Tito family’s beer distributorship behind the house at 1818 Colwell Street are being evaluated as Pittsburgh city historic landmarks. Read the 2021 nomination report [PDF] for additional information on Joe Tito and his enterprises.

© 2021 D.S. Rotenstein